Halloween and Quakers: A Complicated History

Halloween and Quakers

By Amaya Eckersley, Director

The Religious Society of Friends traditionally didn’t celebrate holidays. In early Quaker groups, all days were considered “holy days,” and they believed that God did not intend to have any days be holier than any other. From their inception, those in the Religious Society of Friends also firmly held a value of plainness, which influenced every part of their lives, including their dress, speech, homes and meetinghouses, and treatment of common holidays. However, in the 1800s, Quaker thought around holidays changed slightly. Many began to accept Christmas and Easter as important, or at the very least harmless, holidays, so long as they kept their celebrations uniquely Quaker in nature. During Herbert Hoover’s childhood, it would not have been uncommon to find a plain Christmas tree in meetinghouses, and families would often exchange small gifts. Today, you may find a diverse variety of celebrations in the Religious Society of Friends.

A holiday that took much longer to catch on is Halloween. Halloween presents a multi-faceted conflict for the Quaker faith, and has for centuries. The holiday has strong pagan roots and traditions that have long been viewed as evil by historic Christian groups. While there were attempts to turn Halloween into a Christian holiday, it lacks the strong Christian association that is seen in Christmas and Easter. Finally, Halloween can include dark festivities, glorifying violence and historic tragedies. So where does Halloween sit for the Quakers today?

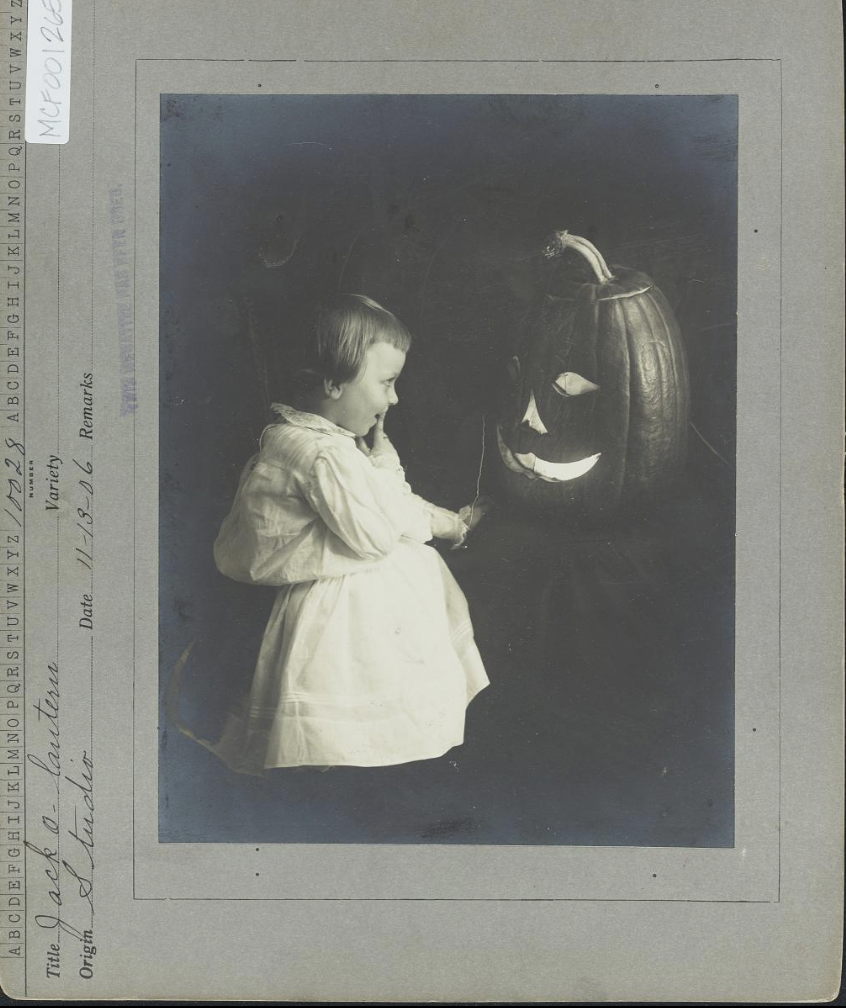

Child with Jack-o-Lantern, ca. 1906. Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Gardens, J. Horace McFarland Company Collection. Sova.aag.mcf_ref15922. Accessed September 29, 2025.

A brief history of Halloween

Halloween comes directly from the pre-Christian Irish celebration of Samhain. There are many traces of Samhain seen in modern Halloween, such as wearing masks, trick-or-treating, and anything involving spirits (1). However, it is impossible to know just how much comes from ancient Irish tradition. Many Samhain traditions were not recorded, or were passed along only in parts through oral tradition. That which was written down may have been burned during the Christianization of Ireland. Between the 9th and 12th centuries, Christian writers did begin to record the celebrations on Samhain, but this is all long after Christian influence (2).

A classic image of a witch flying on a broomstick, ca. 1910. Image in public domain, originally from New York Public Library. https://pdimagearchive.org/images/d2907d3d-2206-46d6-b21c-46ab0182aa1d/.

According to these early Christian writers, Samhain, November 1st, marked the lengthening of the night, a turn to winter (3). In 601 A.D., Pope Gregory the First issued an edict to missionaries instructing them to utilize non-Christian customs and holidays to further conversion (4). This is the very reason why Christmas and Easter have Pagan roots and symbolism, yet are still strong Christian holidays. The edict led to re-workings of various pagan traditions, including many judgements on what would be permissible and what would be rejected as evil or demonic. Catholics in Ireland attempted to do the same with Samhain, creating the Feast of All Hallows (hallows meaning saints).

However, the change in holiday didn’t catch on in the way it did with Christmas and Easter. Instead, the darker celebrations of Samhain migrated to the eve of the Feast of All Hallows, on October 31st. While the Feast of All Saints, also known as All Souls Day, is still celebrated in Catholicism today, the holy day has moved to November 2nd, markedly separate from All Hallow’s Eve, or Halloween. Halloween today remains a reminder of a pagan past, with little importance in the Christian calendar.

Quakers and English Persecution

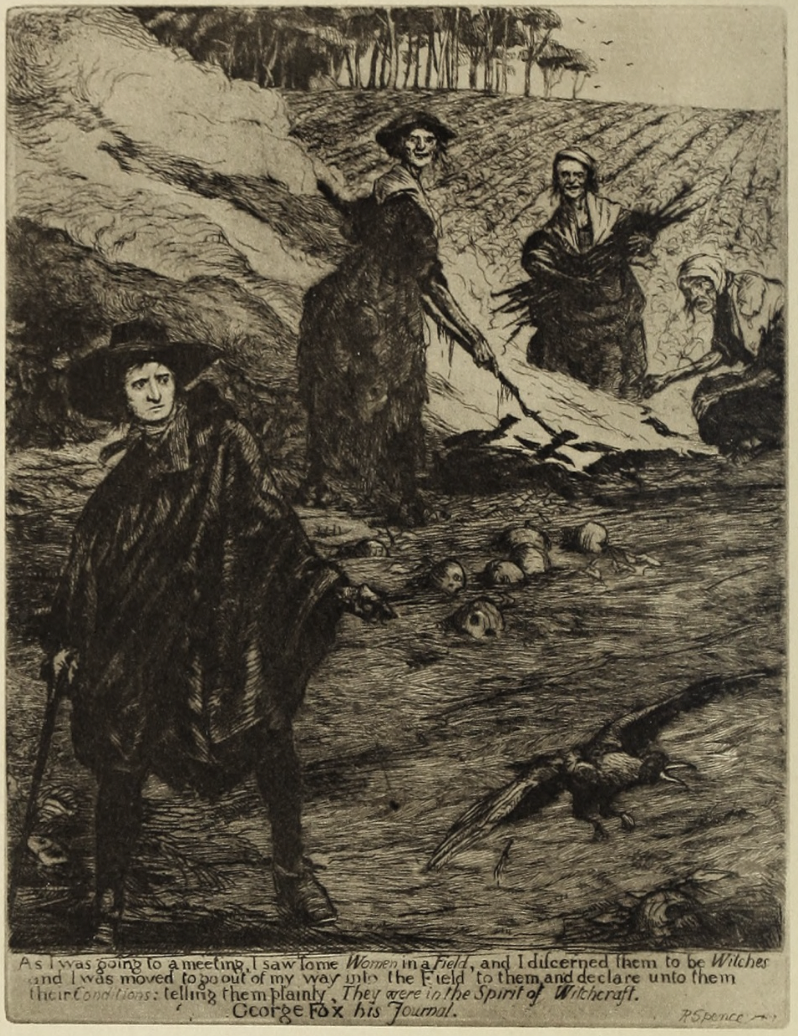

Excerpt from George Fox’s journal and accompanying sketch. Gummere, Witchcraft and Quakerism, front matter.

It is clear why the early Quakers didn’t think it prudent to celebrate. Quakers may also have had a unique aversion to Halloween compared to other groups due to their extensive persecution in England. Today, Quakers are largely understood by non-Quakers as an inoffensive sect of Christianity. The Religious Society of Friends holds peace as a strong guiding moral principle, and non-violence as necessary for the function of the world. These are hardly values to get up in arms about, but back in the 1600s and 1700s the Quakers were viewed as exceedingly radical.

During the witch trials in Europe, men and women were at risk, though women arguably were at higher risk of accusation and death in many areas. When the Religious Society of Friends was founded, the association with witchcraft began immediately. Historian Amelia Mott Gummere, a Quaker herself, has said “There is plenty of evidence that the world regarded the early Quakers as in league with the powers of darkness, because of their strange denial of what everybody owned,” (8). Quaker women were particularly at risk. Witches often were associated with independent, outspoken women who went against the grain of society (9). Since Quaker women were well-educated, were already seen as going against the Christian values of the time, and could even be ministers, the associations came about immediately.

A Quaker woman preaching, ca. 1656. Carel Allard, Egbert van Heemskerck, and Gerard Valck, “Spotprent op de Engelse Quakers, ca. 1656,” Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. https://jstor.org/stable/community.8809235.

How do Quakers celebrate Halloween today?

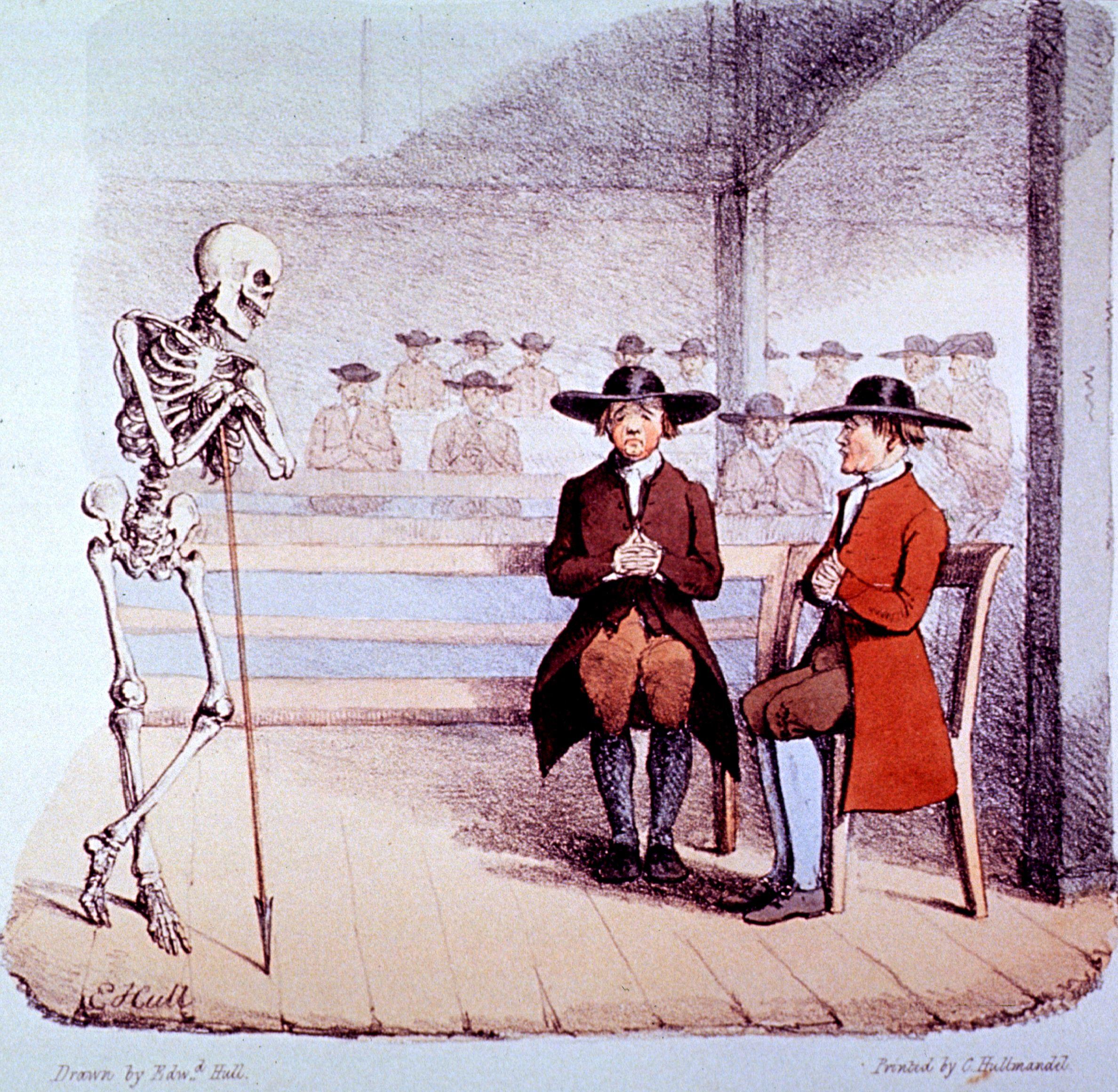

A figure referred to as “Death” approaching two Quakers in a meetinghouse, ca. 1800s. Hull, Edward. Death Saw Two Quakers Sitting at Church. U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM): Images from the History of Medicine. https://jstor.org/stable/community.28557587.

Quakers were obviously not the only people impacted by the witch trials, but it is still a sad and sore history, and one that is often referenced and made light of during Halloween festivities. The “witch” is an iconic representation of Halloween, the first image that many people’s minds go to. The image, originally built off of historic anti-Semitic stereotypes, haunts Halloween just as much as evil spirits, gore, and violence all do (10). However, many Quakers today have found a way to enjoy the fun of Halloween in a manner that works for them and upholds their values.

A writer from the Friends Journal suggests that Quakers should consider the meanings and impacts of costumes in particular, as this directly affects how children and adults alike are representing themselves (11). Superheroes, while they may seem harmless, respond to harm and violence with more violence. As such, they may not be a fit Quaker costume. Monsters, even those such as vampires, might be permissible with adequate discretion. Most importantly, this article instructs parents to not allow blood, weapons, or even racial or cultural stereotypes to be a part of their children’s costumes, and suggests that all Quakers keep as aligned with the Friends Peace Testimony as possible (12). For many Quakers, it seems that the pagan roots of Halloween are far enough in the past that there is little to no concern today, so long as the holiday is kept light, fun, and friendly for all.

Are you a Quaker who would like to share how your family celebrates (or doesn’t celebrate) Halloween? Please contact us! We’d love to hear from you.

Notes

(1): Jack Santino, “Halloween in America: Contemporary Customs and Performances,” Western Folklore 42, no. 1 (1983): 4–5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1499461.

(2): Santino, “Halloween in America,” 4.

(3): Santino, “Halloween in America,” 4–5.

(4): Santino, “Halloween in America,” 7.

(5): Amelia Mott Gummere, Witchcraft and Quakerism: A Study in Social History. Gummere’s point is made multiple times throughout this book.

(6): Susan Wareham Watkins, “Hat Honor, Self-Identity and Commitment in Early Quakerism,” Quaker History 103, no. 1 (2014): 1–16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24896080.

(7): For more information on this specific type of persecution that Quakers faced, see: Gummere, Witchcraft and Quakerism.

(8): Gummere, Witchcraft and Quakerism, 30.

(9): For more information on what actions or perceptions affected the witch trials, see: Alan Charles Kors and Edward Peters, Witchcraft in Europe, 400–1700: A Documentary History.

(10): Salem Witch Museum. “Witch Trials and Antisemitism: A Surprisingly Tangled History.” Accessed September 29, 2025. https://salemwitchmuseum.com/videos/witch-trials-and-antisemitism-a-surprisingly-tangled-history/.

(11): Michael Zimmerman, “Halloween, Quaker Style,” Friends Journal, (October 1, 2010): n.p., https://www.friendsjournal.org/2010085/.

(12): Zimmerman, “Halloween, Quaker Style,” n.p.